Since taking power in 2012, Xi has launched a sweeping campaign against graft and disloyalty, taking down corrupt officials as well as political rivals at an unprecedented speed and scale as he consolidated control over the party and the military.

Now well into his third term, the supreme leader has turned his relentless campaign into a permanent and institutionalized feature of his open-ended rule.

And increasingly, some of the most fearsome tools he has wielded to keep officials in line are being used against a much broader section of society, from private entrepreneurs to school and hospital administrators – regardless of whether they are members of the 99-million-strong party.

The expanded detention regime, named “liuzhi,” or “retention in custody,” comes with facilities with padded surfaces and round-the-clock guards in every cell, where detainees can be held for up to six months without ever seeing a lawyer or family members.

It’s an extension of a system long used by the party to exert control and instill fear among its members.

New detention regime

For decades, the party’s disciplinary arm, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), had run a secretive, extralegal detention system to interrogate Communist Party cadres suspected of corruption and other misdeeds. Officials under investigation were disappeared into party compounds, hotels or other covert locations for months at a time, with no access to legal counsel or family visits.

In 2018, amid growing criticism over widespread abuse, torture and forced confession, Xi scrapped the controversial practice known as “shuanggui,” or “double designation” – a nod to the party’s power to summon members for investigation at a designated time and place.

But the Chinese leader did not abolish secret detention, which had been a potent weapon in his war on corruption and dissent. Instead, it was codified by law, given a new name and placed under the purview of a powerful new state agency, the National Supervisory Commission (NSC).

Founded in 2018 as part of the constitutional revision that cleared the way for Xi to rule for life, the new agency consolidated the government’s anti-graft forces and merged them with the CCDI. The two agencies work hand in glove and share the same offices, same personnel and even the same website – an arrangement that expands the remit of the party’s internal graft watchdog to the entire public sector.

The new liuzhi detention regime has kept many features of its predecessor, including the power to hold suspects incommunicado in custody and a lack of independent oversight.

The lawyer, who requested anonymity due to fears of retribution from the government, said many of their clients had detailed abuse, threats and forced confessions while in liuzhi custody.

“Most of them would succumb to the pressure and agony. Those who resisted until the end were a tiny minority,” the lawyer said.

Liuzhi casts a much wider dragnet than shuanggui, targeting not only party members, but anyone who exercises “public power” – from officials and civil servants to managers of public schools, hospitals, sports organizations, cultural institutions and state-owned companies. It can also detain individuals deemed to be implicated in a graft case, such as businessmen suspected of paying bribes to an official under investigation.

High-profile liuzhi detainees include Bao Fan, a billionaire investment banker, and Li Tie, a former English Premier League soccer star and coach of China’s national men’s team. (Li was sentenced to 20 years in prison for corruption this month.) At least 127 senior executives of publicly listed firms – many of them private businesses – have been taken into liuzhi custody, with three quarters of detentions taking place in the past two years alone, according to company announcements.

State media says the expanded jurisdiction fills longstanding loopholes in the party’s anti-corruption fight and enables graft busters to go after everyday abuse of power endemic in the country’s behemoth public sector, from bribes and kickbacks in hospitals to misappropriation of school funds.

Critics say it is another example of the party’s ever-tightening grip over the state and all aspects of society under Xi, China’s most powerful and authoritarian leader in decades.

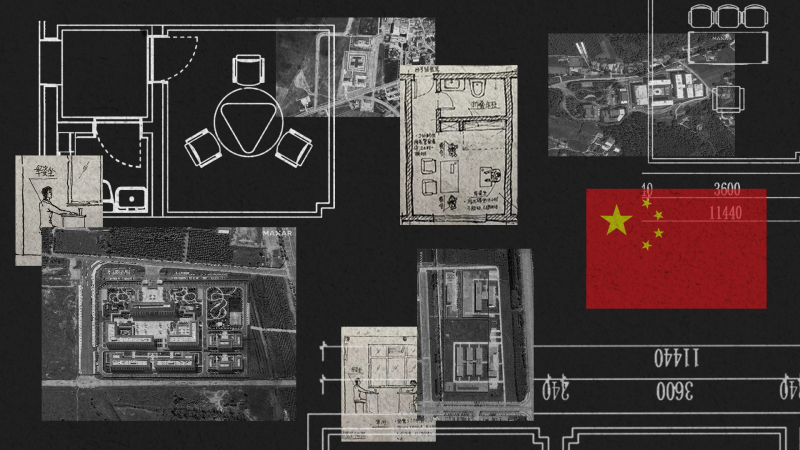

Some of the detention centers built or expanded in China since 2018

The real number is likely much higher, as many local governments don’t publish tender notices online, or delete them after the bidding is finished.

The spate of construction appears to be largely driven by a surge in demand for detention cells due to the NSC’s new broad remit, as well as efforts to make liuzhi facilities more standardized and regulated than the hotels and villas often used for shuanggui, the documents revealed.

Soft padded rooms

An analysis of the tender notices shows a lull in construction during the pandemic, but the number of projects picked up again in 2023 and 2024. More detention centers have been built, and more funds have been allocated, in provinces and regions with a higher percentage of ethnic minorities.

Shizuishan, a city in the northwestern region of Ningxia – the official heartland of the Hui Muslim minority – was approved to build a 77,000 square feet liuzhi site with a budget of 20 million yuan ($2.8 million) in 2018, according to a government notice.

The document provides a rare glimpse into what the interior looks like. All detention cells, interrogation rooms, and the infirmary must have fully padded walls, cabinets, tables, chairs and beds, with all edges rounded for safety.

No exposed electrical wiring or power sockets are allowed, and floors must be treated with anti-slip surfaces. All ceiling-mounted installations, including surveillance cameras, lights, fans and loudspeakers, must incorporate “anti-hanging designs.” In the bathrooms, washbasins and stainless-steel toilets must be fully padded too, while showerheads and surveillance cameras must be mounted on the ceiling, according to the notice.

These maximized safety features are designed to prevent detainees from taking their own lives – an issue that had long dogged shuanggui detentions.

But Shizuishan’s liuzhi center turned out to be too small for the influx of detainees. In June, the city published another notice seeking to expand the facility to address the problem of “insufficient facilities and equipment.” The project includes a new building for interrogation, a new staff canteen and reconfiguration of existing buildings to create more detention cells.

The party never published official figures on shuanggui detention, and the numbers on liuzhi are nearly as elusive. In 2023, the only year national data was available, 26,000 people were detained by the NSC and its local branches across the country.

Provincial data, although patchy, has pointed to a sharp increase in the number of detentions. In the northern region of Inner Mongolia, 17 times more people were placed under liuzhi custody in 2018 than those subject to shuanggui in 2017, according to the region’s supervisory commission.

Dingxi, one of the poorest cities in the northwestern province of Gansu, said its 305-million-yuan ($42 million) detention center would be built following requirements specified by the CCDI and NSC to achieve the “standardized, law-based, and professional operations” of the liuzhi facility.

The massive complex, featuring 542 rooms, will include 32 detention cells, accommodation for investigators and guards to live on site, as well as other facilities to meet their daily needs, according to a 2024 budget document of the city’s anti-graft agency.

Life under liuzhi

Chinese officials and state media have hailed the transition from shuanggui to liuzhi as a crucial step toward what they describe as “the rule of law in anti-corruption work.”

The shuanggui system had long been criticized for using threats, intense pressure or even torture to secure confessions. A 2016 report by Human Rights Watch documented 11 deaths in shuanggui custody from 2010 to 2015, and numerous instances of abuse and torture.

Unlike shuanggui, which had no legal basis, liuzhi is inscribed in the national supervision law – introduced in 2018 to regulate the NSC.

The law bans investigators from collecting evidence through illegal means such as threats and deception; it prohibits insulting, scolding, beating, abusing and any form of corporal punishment of those under investigation. The law also requires interrogations to be recorded on video.

But legal experts say the legislation only wraps a thin veil of legality around a detention regime that operates outside the judicial system, lacks external oversight and remains inherently prone to abuse.

“In the past, it was extra-legal. Now, some critics call it ‘legally illegal,’” said a Chinese legal scholar who has studied the NSC. They spoke on condition of anonymity, citing fears of government retribution.

China’s opaque court system, which answers to the Communist Party, already boasts a conviction rate above 99%.

But unlike criminal arrests, liuzhi takes place outside the judicial process and does not allow access to legal representation, raising concerns for potential abuse of power, said a second Chinese scholar who also requested anonymity.

In September, Zhou Tianyong, a top economist and former professor at the elite Central Party School, where the Communist Party trains its senior officials, warned that local authorities had been using corruption probes to extort money from private entrepreneurs to fill their strained coffers.

In a viral article that was later censored, Zhou called for an end to the practice by local anti-graft agencies of detaining businessmen on suspected or trumped-up bribery charges and forcing them to pay for their release. “If (this trend) spreads, it will undoubtedly lead to another disaster for the national economy,” Zhou wrote.

In recent years, allegations of abuse and forced confessions have emerged in multiple liuzhi cases publicized online.

Among them is Chen Jianjun, an architect-turned-local official who claimed he was deceived and forced into making false confessions of bribe-taking while detained under liuzhi in 2022 in the northwestern city of Xianyang.

During his six months of detention, the 57-year-old was watched by rotating pairs of guards around the clock and forced to sit upright for 18 hours a day without moving or speaking, with any slightest bending of his back immediately met with reprimands from the guards, according to a written account of his experience posted on social platform WeChat.

Chen was only allowed to sleep for less than six hours a day under bright lights that were never switched off; in bed, he must lie on his back and keep his hands above the blanket in sight of the guards, he wrote.

“The prolonged torment left me physically and mentally exhausted, with blurred consciousness, a mental breakdown, chaotic thoughts and hallucinations,” Chen wrote, adding that by the time he emerged from liuzhi, he had lost 15 kilograms.

In 2023, Chen was sentenced to six years in prison for accepting bribes of 2.5 million yuan ($340,000). He appealed and is waiting for a ruling, according to Caixin, a business magazine known for its investigative reporting.

The Chinese lawyer who represented officials in court after they were released from liuzhi custody said it was common for detainees to be forced to sit in one position for up to 18 hours a day.

“They had to sit continuously without moving, causing severe pressure ulcers on their buttocks. Some medicine would be applied, but they were made to continue sitting, leading to further deterioration. It was extremely torturous,” they said.

Some clients were also given very little food until they confessed, causing malnutrition and a host of other health problems, the lawyer said. “Many people eventually developed auditory hallucinations and felt like they were losing their minds,” they said.

According to the lawyer, another tactic commonly used by investigators was to detain an official and their spouse simultaneously, even if the spouse did not hold public office.

It’s a two-pronged approach: investigators can try to gather clues about the official’s alleged transgression from the spouse; while the spouse can be held hostage to pressure the official to confess, the lawyer explained.

In some cases, investigators had also threatened to detain officials’ children for interrogation, the lawyer added.

A draft amendment to the national supervision law, which is under review by China’s top legislature, appears to nod to concerns of potential abuse. It added a clause that requires investigators to carry out investigations in a “lawful, civilized and standardized manner.”

But the draft proposal has ignored calls to allow access to legal counsel during liuzhi detention. Instead, it has suggested extending the maximum detention period from six months to eight months, if the suspect is likely to be sentenced to a prison term of 10 years or longer; the entire liuzhi period can be reset and restarted if new offenses are discovered, meaning a maximum of 16 months of custody, according to the proposal.

The draft amendment has sparked heated debate and criticism from Chinese lawyers and legal scholars, who say the powers granted to investigators during liuzhi have far outweighed the protection of detainees’ rights.

“Prolonged detention and interrogation present an extreme test that surpasses the physical and mental limits of the detainee,” Dacheng, a Beijing-based law firm, said in an article on its social media account.

“Under such extreme conditions, where both the body and the mind are pushed to their limits, it becomes increasingly difficult to tell whether the detainee is giving an ‘honest confession’ based on facts or opting for ‘full cooperation’ by compromising the truth under unbearable pressure.”