For more than 60 years Cuba has buckled under US economic sanctions and its own government’s missteps. Life on the communist-run island could soon become even more grueling.

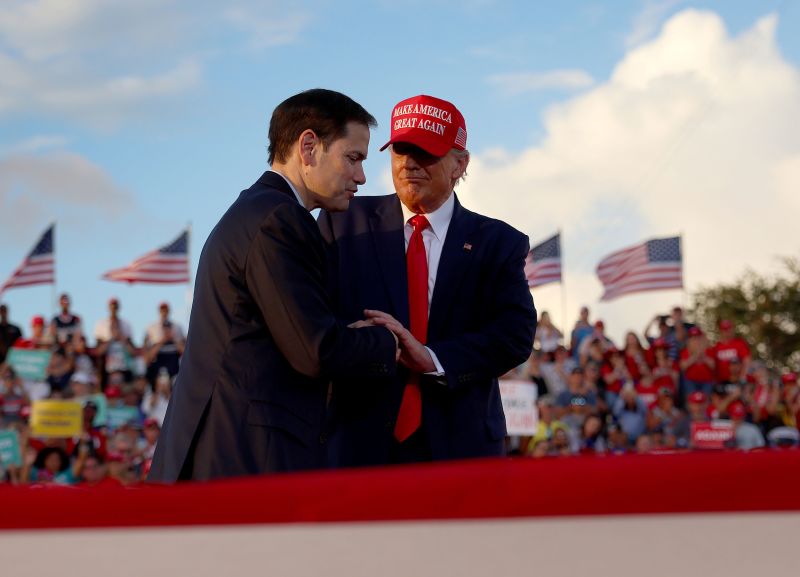

One of the Cuban government’s most formidable adversaries, Sen. Marco Rubio is set to become secretary of state under Donald Trump, something that does not bode well for the already flatlining Cuban economy.

The son of Cuban exiles, Rubio has long made it his mission to ramp up the US trade embargo on Cuba. If confirmed, as is widely expected, Rubio will be perfectly situated to further tighten the screws on Cuba perhaps to the island’s breaking point.

“He has reached the pinnacle of power and position in the US government that he has never held before and he is going to be putting it to Cuba to prove his reputation as an extremist hardliner on Cuba,” said Peter Kornbluh, co-author of “Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Secret Negotiations Between Washington and Havana.”

If confirmed, Secretary of State Rubio will face far more pressing issues like Russia’s war in Ukraine, conflict in the Middle East and countering growing Chinese influence in the world, particularly in Latin America.

But Cuba has been central to Rubio’s long climb from city commissioner in West Miami to state representative to US senator to Republican presidential candidate to now being selected for secretary of state. The second paragraph of Rubio’s Senate bio says he first entered government “in large part because of his grandfather who saw his homeland destroyed by communism.”

The decades-old joke in Rubio’s hometown of Miami, a refuge for exiles who fled socialist regimes in Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua, is that it is the only city in the United States with its own foreign policy.

That quip no longer seems so facetious as a son of exiles who fled their homeland prepares to become America’s top diplomat. As secretary of state, Rubio could run point on devising additional economic sanctions on Cuba, increasing funding for dissidents and pro-democracy programs that Havana considers tantamount to regime change, and further restricting US travel to Cuba.

Under the Biden administration, the US again expanded flights to destinations across the island, opened up online payment systems to Cuban entrepreneurs and relaxed restrictions on US citizens traveling to the island.

Rubio though has been a fierce critic of Americans visiting Cuba, saying in 2013, “Cuba is not a zoo where you pay an admission ticket and you go in and you get to watch people living in cages to see how they are suffering … You’ve left thousands of dollars in the hands of a government that uses that money to control these people that you feel sorry for.”

Raising the issue of Cuba

Those who have studied his career say there is no more personal issue for Rubio than ending what he sees as a tyrannical dictatorship 90 miles from US shores.

As secretary of state, Rubio would be able to apply pressure on the island’s communist leadership and their allies much more directly. It would be hard for a country as tied to the US as economically as, say, Mexico, which has in recent months sent Cuba hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil and paid the island to supply them with doctors, to ignore requests from a US secretary of state to cut support to Havana.

And while Trump has hobnobbed with authoritarian heads of state like Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un, he has not shown any willingness to do so with socialist leaders in Cuba or Venezuela, which could hurt his growing support with the Latino community in the US.

Further sanctioning the already ailing Cuban economy could backfire though.

“There are no plans that I’m aware of for what to do with a failed state 90 miles off US shores,” says Ricardo Herrero, executive director of the Cuba Study Group that promotes dialogue between the two governments. “Which is what Cuba appears to be approaching or at least seems to be much closer to becoming — a failed state — than a Jeffersonian democracy.”

Cuban officials, who until recently often derided the Florida senator as “Narco” Rubio, a reference to his brother-in-law’s cocaine smuggling conviction in the 1980s, have shrugged off the threat of further Trump sanctions but said they are open to negotiating directly with any US official, even Rubio.

Still, Cuba’s leadership has made it clear that no amount of US pressure will force them to hold multi-party elections or release political prisoners, as US administrations going back to Eisenhower have demanded.

“The results of these elections are nothing new for us,” Cuba’s President Miguel Diaz-Canel told state-run media in November following Trump’s election. “The country is ready. We will continue on, without fear, trusting that with our own effort, with our own talent, we can get ahead.”

But the worsening economic reality on the ground stands in stark contrast to that bravado.

On Wednesday, a month before Trump is set to take office, once again the lights flickered off in all of Cuba. The latest blackout, caused by a power failure at an aging, Soviet-era plant, was the third island-wide outage in as many months.